The Milei Experiment: How Did We Get Here?

(Any views expressed in the below are the personal views of the author and should not form the basis for making investment decisions, nor be construed as a recommendation or advice to engage in investment transactions.)

I want to start by apologizing to my Argentine compatriots: I won’t be sharing anything groundbreaking or revelatory, and this won’t be a brilliant piece of analysis predicting the future. I’ll make big and probably unfair omissions. I express opinions I stand by. This article serves as a fun literary exercise for me to respond to my diverse group of trader friends from around the world—who, luckily, are many and come from various backgrounds—and lately they inevitably ask me, “What the hell is going on in Argentina?”

“The Argentina is that strange place where all theories go to die,” wrote Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner (twice former president, current vice-president, and undisputed leader of the ruling political space in transition) on her blog personal in 2020. In that speech, she defends that statement as one of her certainties at the time. “That’s why the issue of the bimonetary economy is, without a doubt, the most serious problem our country faces.”

I’ll kick off with a fun fact: According to a report from Bloomberg Argentina is one of the countries with the most physical dollars outside of the United States. In 2023, it is estimated that Argentines have around $150B in physical dollars, representing approximately 8-10% of the total physical dollars in the world. Yeah, read that again.

Translated into Argentine: There’s a lot of cash “under the mattress” and not inside banks.

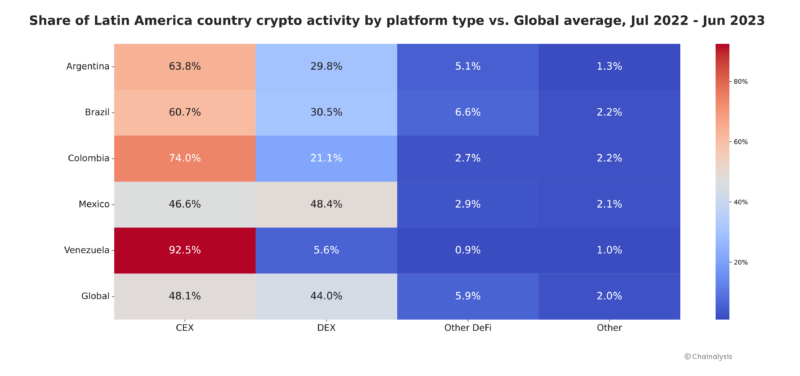

Much of this stems from an unavoidable truth: Argentines have lost trust in banks. That’s also why Argentina is one of the countries with the highest organic adoption of cryptocurrencies. I’ve paid for medical consultations, tax advisory services, weed, and even a new TV with crypto—all peer-to-peer. Personally, I’ve never had a credit card, and like many friends and colleagues, I don’t keep my savings in banks.

The infamous financial crash of Argentina in 2001-2002— a complex scenario partly caused by defaulting on external debt— ironically occurred under a government that attempted to “dollarize.” The value of the Peso was pegged to the dollar at a 1:1 ratio, just like the stablecoins we know and love (or hate depending on your level of Bitcoin fanaticism). We might need to review those tokenomics, but that’s not my job here today.

On the political front, the oscillating, pendular nature of consensuses and a well-executed counter-narrative, coupled with a regional shift towards what I’ll define as “modern Latin American socialisms,” allowed Nestor and Cristina Kirchner 12 uninterrupted years in power.

By the end of 2015, with consistent growing inflation, currency restrictions that made it impossible to buy dollars, multiple suspicions of corruption, and a myriad of intrigues—expectable, in hindsight, from states that lack sufficient alternation—they lost the elections, and Mauricio Macri (from the well-known local 1% family) took office. He lifted the currency restrictions and indebted Argentina by $57 billion with the IMF, only to leave everyone scratching their heads when he reinstated the currency controls, one of his main campaign promises. Long story short: He played the financial market like a game and lost, thus leaving a huge debt an already-weakened country..

As a consequence, and keeping an eye on society’s pendular logic, Cristina Kirchner would reclaim power again for his third presidency, this time with a phenomenal twist: She would run for the upcoming elections as vice president and handpicked the next president to be the face of candidacy. Sun Tzu intensifies.

Fast-forward several more years. She is now the vice president of a puppet president who barely appears on TV because every second of his face is another lost vote. There’s inflation. Ridiculous tax burdens create more informal employment, resulting in inadequate state revenue. There’s also no credit or real access to information or financial instruments, nor easy ways to trade on international markets. Their solution? Printing money. Through printing, through seigniorage—and then by trying to stop circulation with ticking time bomb instruments like the LELIQ (short-term government bonds) resulted in a 150% annual inflation rate, 50% poverty, and a deep-seated resentment shared against the “political class.”

“Government checks” (stimulus, welfare, public jobs, retirements) vs private sector jobs, in millions of people, by @fernandoMarull

For the average young citizen, there are no genuine ways to start a business or even access genuine private employment, and not only that: a certain degree of fiscal ninjutsu and a solid accountant are necessary to navigate the unbearable tax burden on any small or medium-sized company (I’ll stick to what I know firsthand). The average salary hovers around $300. The average Argentine has seen politicians as the only “caste” (a word with immeasurable penetration during this campaign) benefiting from the “upward social mobility” they preach—always and exclusively within the endogamous and often opaque circles of state dependencies.

Bank assets and liabilities. In blue, private credit; in black, short-term central bank + treasury bonds; in yellow, LELIQs + treasury bonds + private credit

Even those of us who were children in Argentina in 2002 (I was born in 1993 and saw my dad buy printers and sell them on the same day so we could eat during that time) do not know a world without constant growing inflation, with access to credit, or with basic financial guarantees. Much less a world with aspirations to buy a house or embark on a project that requires bureaucratic logistics, and sometimes even buying a car.

// I’d like to delve into this “generational dysphoria” between the possibilities projected 50 or 70 years ago and the current reality someday. I think there’s a lot of that in this global phenomenon. The dysphoria between what ‘we were promised’ was possible when we were kids versus the world ‘they left us,’ which has little to do with that worldview of yesteryear.

And almost like a running gag from a sitcom, 21 years after the crisis (Fibonacci would be proud), Javier Milei will be the new president as of December 10. Paradoxically, one of the most prominent slogans of the self-proclaimed anarcho-capitalist during the campaign was… yes, “dollarization.” History never repeats, but it often rhymes.

The last time I went to pay the rent for my apartment (a high-rise in the capital city), I paid the equivalent of $100 USD in Argentine pesos. A similar rent in any other metropolitan city in the world would be around $450. In Madrid, perhaps $1200. In Hong Kong, you’ll pay at least US$4.50 per square foot monthly. Recently, I worked in Spain, and of the several times I’ve been to Europe, that was when I heard inflation mentioned the most – and it stood out. Yet, Spainards were really stressed out about it – with at least 15 times less inflation than what Argentina is currently enduring, generously taking their highest figure of the last years (10%).

The cause of this is one of the latest hits from the “caste“: the infamous “Rent Law,” another example of the disproportionate level of state interference in private transactions. It not only forcibly controls rent prices but also obliges parties to agree to the contract in Argentine pesos—yes, the same peso that devalues 10% per month and compoundingly surpasses 150% annually. This obviously caused a habitational crisis due to the lack of supply.

The owner of my apartment (an 80-year-old single man who happens to enjoy trading in the local stock market, which has led to us sharing some laughs and even a kind of complicity despite the generational gap) kindly informed me that he did not plan to renew my contract at its end. It wasn’t profitable for him to rent out his apartments, and he planned to sell them. Yes, to invest in Argentine stocks.

Despite being an old man who often jokes about losing a fair amount of money “gambling the market,” he couldn’t help confessing in recent months that it had been one of the most profitable periods of his life. All this preamble is solely to provide context and market research value to the remark he let slip one of the last times we met: “Lately, it’s as if the croupier is telling me where to place the chip.”

In the Argentine cultural DNA, wit in the face of adversity (problem-solving as a survival method) coexists unequivocally with a truly unique and often misdirected (or directed) passion that is pathologically polarizing and divisive. River vs. Boca. Maradona or Messi. Kirchner or Macri. X vs Y.

From as far back as I can remember, the consensus constructed (but also shaped by the state, when functional) has been that there’s no room for fence-sitters. The expectation is for everyone to take a strong stance and then become a fanatic, sometimes ignoring the contradictions of the rather dogmatic discourse that repeats itself in this exercise of zealotry.

In hindsight, I would now say it’s wiser to invest one’s energy in matters that, at some point, propose tangible deadlines or realistic end goals. But that same logic which makes us so assertive and cunning for prestidigitation – often dissipates in the fervor of the fantastic narratives that politicians proposed to us throughout its various casts.

Many vulnerable sectors have been the shock troops of these narratives, and now, facing an economic catastrophe, they begin to perceive themselves as the fuse, the ‘exit liquidity,’ the losing link against the leaders who speak only in slogans. Everyone feels betrayed at some point.

Over the years, these leaders, judges, prosecutors, political operators have amassed fortunes well beyond their already exorbitant salaries—while the state, forcibly, has nationalized and socialized the spending of the politicians’ extravagant lifestyles. They feed their addiction to printing money from the Central Bank at the expense of melting the savings of the Argentine people.

They’ve also made us vigilantes of our compatriots during the world’s second-longest lockdown. We couldn’t say goodbye to our loved ones, while we discovered that the President was hosting parties at his house. Or that, in the face of vaccine shortages, government officials and friends of the powerful were preferentially vaccinated in what the press dubbed a ‘VIP Vacunation Center’‘ Or while videos leaked of officials literally unloading bags of dollars and rifles in a church to hide them. Every Argentine holds a personal grudge or a great disappointment with some aspect of all this.

Milei emerges in this context of weariness. And in line with the current pendulum of (apparent) ‘outsiders without their own structure’ like Bolsonaro or Bukele, Milei was extremely effective in channeling this message of disappointment and frustration since his TV appearances increased in frequency, around 2020.

His main slogan was always verbatim “We have to demolish the Central Bank.” Here’s a memorable TV moment from 2018 that already predicts the penetration of the message back then, when no one in their right mind would have thought that this same guy with a bat would win the presidency with 55% of the votes. Here we stand today, days away from his inauguration. Milei is the most voted president in Argentine history in absolute terms.

Now, Milei. At the peak of his television prominence and the moral-economic downfall of the ruling party, he decides, in his words, to ‘get into the mud.’ He runs for deputy in 2021 and, after winning, announces that he will raffle off his entire salary every month.

With the deepening of the aforementioned national crisis and a growing hype around his slogans—radical but definitely resonant for a people plunged into helplessness—Milei announces his presidential campaign. “The political caste is a three-headed hydra: politicians, businessmen, and unionists (…) The only way out is with a monumental adjustment, and politicians have to pay for that adjustment.”

“Politicians are parasites living off the State,” Milei continues, furious on some late-night show. And he’s speaking directly to the muggles on the other side, who witnessed the ridiculous enrichment of politicians and their usual megalomaniac affairs. That discourse penetrates, even ignoring some of the underlying connotations. I mean, let’s say: “We’re going to make a giant shock adjustment” is not the typical slogan that a campaign advisor would recommend to win an election.

Official and opposition media, partly responsible for bringing him to TV to portray an “irritable and loud neo-liberal archetype,” began to feel threatened after his candidacy and found his Achilles’ heel: Milei has a strange compulsion to translate very abstract concepts of free-market ideology from the ideological/figurative realm to the earthly/explicit with very few filters for a candidate.

In numerous interviews, Javier Milei has responded to rather pragmatic questions with theoretical narratives, often alarming. Among the most noteworthy are some about organ sales (“Organs are private property that a person can sell like any other”) or that child adoptions, managed by the state, can turn into agreements between private individuals.

Since his candidacy for president, Milei has faced what we colloquially define here as ‘lack of machinery.’ This means a lack of political and party structure, local and regional candidates across the country, and poll watchers for the vote count. However, his extravagance, his irate statements, and finally, his proposal, had an enormous impact against odds and political rulebooks

That ‘machinery’ was quickly assembled with what was at hand. In Milei’s ranks, there are not only citizens fed up with poor governments but also cosplayers, alt-right youtubers, defendants of genocides from the last military coup in the 70’s, and a new cast of extravagant characters. Far from judging their professions or abilities, the truth is that, at some point in the campaign, every Argentine questioned whether this crew had the expertise to decipher the workings of the true gears of the State, operate in time, and with the necessary cunning.

For this reason, and facing the runoff election (a two-round electoral system that pitted him against the current Minister of Economy, Sergio Massa), Milei inevitably had to negotiate with “the caste” he swore to destroy. This is where former president Mauricio Macri, (spirit animal of the PRO, the “other major opposition bloc” to Kirchnerism) expresses his support and calls for a vote for Milei, almost at the last minute, and confusing both allies and opponents in a fun “signature” vendetta, in line with his Calabrian heritage.

With the intention of defining the election, one of the heads of “the hydra,” the repetitive Argentine bipartisanship, lined up behind (or beside?) Milei. Each one will interpret whether this happens within the framework of the Art of War, good democratic faith (hmm…), or if these are simply the ‘antibodies of traditional politics’ trying to neutralize or dilute Milei’s intention to dismantle the intricate state machinery. The truth is, Milei needs them, and in that need, he is forced to transgress his own electoral slogan: “A different Argentina is impossible with the same old faces.”

Nevertheless, his victory is unprecedented in local history and perhaps in modern history: a self-described anarcho-capitalist is now president. It reflects widespread discontent with traditional politics. However, some of his proposals have never been tested, and his lack of experience in public management—with the emotional intelligence that is especially required in Argentina—raises doubts about his ability to carry out his program.

In this election, people voted “thinking with their pockets.” The overwhelming majority that voted for him need urgent solutions to get their lives in order. But the real uncertainty lies in whether Milei is capable of sifting, organizing, and leading—in other words, being a founder of his real power base—or if he will be hostage to statements from third parties (or even his own) that could quickly alienate or upset the 55% that voted for him as an expression of discontent with the current system.

Fourteen million votes constitute a gigantic and historically unprecedented majority, not necessarily homogeneous, that may not agree on much more than the underlying premise: deactivating the mechanisms that gave the “political class” the tools to print money and systematically impoverish through seigniorage, the excessive use of state funds, and, primarily, the lack of solutions to local and external indebtedness.

Operating loss of public companies since 2008, in millions of euros.

“The State is the problem, not the solution” is a powerful slogan that we have also heard a lot this campaign. One of the most controversial aspects of Milei’s discourse is the closure of the State TV Channel, Aerolíneas Argentinas, and above all, the removal of a large number of ministries. Here is a viral video on the subject, where he forcefully describes the current size of the state and the downsizing he proposes.

A ‘hot spot’ in the proposal is the sale of YPF, the main Argentine oil company, of which the State owns 51%. Milei’s supporters argue that the sale of YPF would allow the State to save money and reduce bureaucracy. They also claim that the company would be more efficient in private hands. Opponents of Milei argue that the sale of YPF would be a strategic mistake. They argue that the company is essential for Argentina’s energy security and that its sale could leave the country in foreign hands.

In the current geopolitical context, the sale of certain strategic assets that Argentina holds (water, lithium, oil) could be especially controversial. China, for example, is seeking to increase its presence in Latin America and could leverage the sale of YPF to increase its influence in the region.

According to Milei, the plan is not to sell them immediately but to increase their value and then sell them to restore fiscal balance. We still don’t know how much of this will be achievable in the realm of realpolitik. What is certain is that after Milei’s victory, virtually all Argentine stocks are, obviously, pumping.

The truth is that the market is positioning itself rapidly in the face of Milei’s triumph. There is also a wing of traders, market analysts, some with significant clout, who predicted a technical floor in the Argentine Great Bear Market long before the existence of a “presidential Milei”.

One of them is Carlos Maslatón, one of the most prominent local Bitcoin OGs and liberal political blogger, who made a famous Elliot Wave count (astonishing) in April 2020. In that forecast, sustained since then and often mocked by his colleagues, he predicted—and still maintains—that “beyond political leadership, Argentina has completed a 55-year bearish cycle on Oct 2022.” Fibonacci says hello again.

All of this is based on a very resonant concept that this analyst mentioned a few years ago: that the market is a supra-structure of politics. And not exactly the other way around, as it seems to have culturally consensuated. There are bullish people, as there are skeptical ones. The truth is that the level of mystique in Argentina is such that an Elliott Wave count on a napkin can also become a cool enough concept to wear on a T-shirt, as a niche nod to bullish expectations among surprisingly young people.

On the other side of the spectrum, in the realm of skepticism, there’s this amusing report from Morgan Stanley (p.16) that establishes three decisive rules for doing business in Argentina: “Argentina is always a trade, never an investment. Look only for asymmetries, not symmetry—Argentina is not a carry trade. And do not underestimate the politicians’ ability to change the rules of the game.”

The last (or first) great challenge for Milei is governance. Many (if not all) of these reforms require passage through parliament, a parliament in which his fledgling party, with its short political career, is simply unable to garner majorities to enact these changes. And let’s remember: in front of him stands a massive quorum body that will very predictably do everything possible to obstruct these reforms and strip him of governance.

Here’s how the two chambers of Parliament look after the elections, with Milei’s space in purple, the Kirchnerist space in blue (likely not supportive of the initiatives), and in yellow, Macri and the PRO. From this, the scenario is fragmenting and subdividing every minute that passes. If Macri contributes his own bloc to approve the laws, he will likely ask for something in return. We’ll have to see what. Otherwise, it will be impossible for Milei to govern without “emergency necessity decrees”, a rather unpopular practice.

On the other hand, both Milei’s slogans and the popular mandate supporting him have been decisive in the elections, making it easy to be exposed when attempting to obstruct laws without the necessary acrobatics. Argentines are truly fed up with the constant ideological overload and its contrast with the lack of tangible solutions to their everyday problems, which are far too many.

World markets have started to peek into Argentina. There’s a lot at stake for a country that was once one of the world’s top 10 economies before becoming one of the top 3 countries with the highest inflation on Earth.

There’s an old statement in Argentine political culture, the so-called “Baglini’s Theorem”: it claims that “the further one is from power, the more irresponsible political statements become; the closer, the more sensible and reasonable they turn.”

Milei’s premise to destroy the Central Bank and “dollarize,” understood as making the dollar the official currency, has slowly shifted towards confirming the abolition of the peso but not dollarizing, rather allowing “free competition of currencies.” There’s some discursive magic hidden there because, de facto, Argentines save (if they can) in dollars.

Diana Mondino, recently announced as Argentina’s future Chancellor, stated at LABITCONF, “Anyone who wants to make a legal contract in bitcoin will be able to do so.”

Caution. This should be read as: the state would not interfere in contracts agreed upon in bitcoin—where, for example, there is currently no existing regulation right now. Remember, we’re talking about a country that, in the daily exercise of escaping the highly-melting Argentine peso, seeks refuge in USD and, increasingly, in cryptocurrencies.

Does this mean that Milei is a new Bukele, who will buy $BTC from the State and make it legal tender? Probably not. Will this alleviate some of the pre-existing friction for businesses in currencies other than the peso? Most likely.

Milei’s victory in itself—does it signify a conscious paradigm shift for Argentina? Is it another mechanical swing of the pendulum to Fibonacci’s rhythm? Or is it simply an all-in move by a society that has been living on the brink of collapse for at least a decade and has started to spice up its “risk profile” when evaluating electoral offerings?

Milei takes office on December 10th, and in due course, we will have answers. But living here, in a sensation that borders on complicity or psychosis—we all know that in one way or another, Milei is an experiment. One that is certainly unpredictable.

Lost somewhere in that collective neurosis, in that irrational passion, in that creative galaxy of great talent and unique personality that is this place, is my deepest wish, like that of many, that this be the beginning of a new chapter for my generation and for my country.

Over the next four years, we will find out if a wild-haired anarcho-capitalist wielding a chainsaw in his campaign rallies, dreaming of breaking the Central Bank like a piñata, or speculating theoretically about organ sales – was finally the rupture that the very young Argentine democracy needed to embark on for a path of alternation and consensus for this new chapter of its history.

Because at the end of the day, and in Cristina’s own words… Argentina is that strange place where theories come to die.

Mufa.

Community Contributions are just that. Contributions from our community members. If there is a topic you’d like to explore, let us know by filling out this form.

To be the first to know about our new listings, product launches, giveaways and more, we invite you to join one of our online communities and connect with other traders.

For the absolute latest, you can also follow us on Twitter, or read our blog and site announcements. In the meantime, if you have any questions please contact Support who are available 24/7.

The post The Milei Experiment: How Did We Get Here? appeared first on BitMEX Blog.

BitMEX Blog